Mark Sobel at OMFIF discusses the likelihood of a new Plaza Accord to depreciate the dollar. Given one would need Euro area and Chinese agreement, the assessed likelihood is low

A Mar-a-Lago Accord would also be inconsistent with Europe’s cyclical situation. A devalued dollar would be tantamount to a stronger euro. That could be achieved by higher ECB interest rates and/or fiscal expansion in key European nations. But the ECB is now cutting rates given weak European economies and key countries such as Italy and France lack fiscal space.

G3 foreign exchange market jawboning and interventions, absent changes in fundamentals, are largely ineffective. Of course, exchange rates are driven by the entire balance of payments, often reflecting interest rate differentials, and thus it is almost impossible to foresee how capital flows and exchange rates might respond to any agreement.

Would China agree to an accord?

Trump’s ‘devaluation’ rhetoric is heavily aimed at China. China was not a party to the Plaza Accord but it would need to be central to a Mar-a-Lago Accord.

…

A weakening renminbi poses conundrums for Chinese authorities. The renminbi is already falling against the dollar, towards 7.3 currently, reflecting in large measure general dollar strength and anticipation of tariffs (Figure 1). But sharp depreciation against the dollar runs the risk of spawning a massive one-way capital outflow as happened in 2015-16, an experience China doesn’t want to see replicated. The authorities might have some temptation, however, to let the renminbi fall in a restrained manner to offset the impact of tariffs and send Trump a message.

This article spurred me to examine the US effective exchange rate, measured using (the conventionally used) CPI and unit labor costs (the latter more relevant for evaluating “competitiveness” — see discussion here).

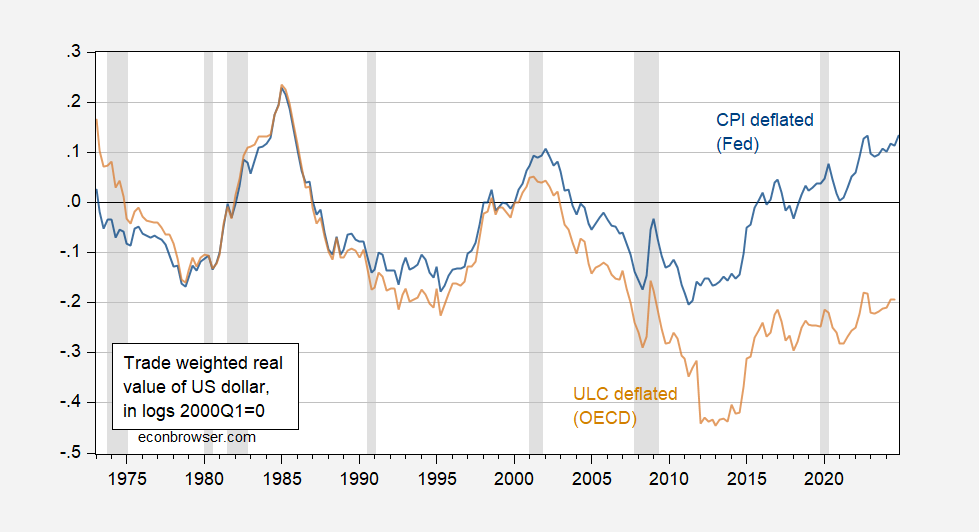

Figure 1: CPI deflated trade weighted value of US dollar (blue), and ULC deflated value of US dollar (tan), both in logs 2000Q1=0. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. CPI series is Fed goods trade weighted series spliced to goods and services trade weighted series at 2006M01. 2024Q4 observation is for October-November. Source: Federal Reserve Board, and OECD, both via FRED, NBER, and author’s calculations.

So on both CPI deflated and ULC deflated (“competitiveness”) terms, the dollar is indeed not as strong as it was in the mid-1980’s. So why the Trumpian fixation on the exchange rate? Are exchange rates essential to the trade balance? I’d say no, having been the contributor to many papers on the elasticities approach to trade flows (see here and here). However, I’d also say that at the medium run, private saving relative to investment, and public saving (ie, the budget balance) are going to be key determinants of the current account and indirectly then the trade balance (as in the IMF’s earlier Macroeconomic Balance approach underlying CGER, and Chinn and Prasad (2003), and various Chinn-Ito papers [1] [2] [3] [4]).

The Trumpian idea of forcing a depreciation of the dollar will then likely have little medium term effect on the trade balance in the absence of somehow adjusting macroeconomic balances (admittedly, throwing the US economy into a recession would tank investment, (SI) would increase and ceteris paribus the current account improves).

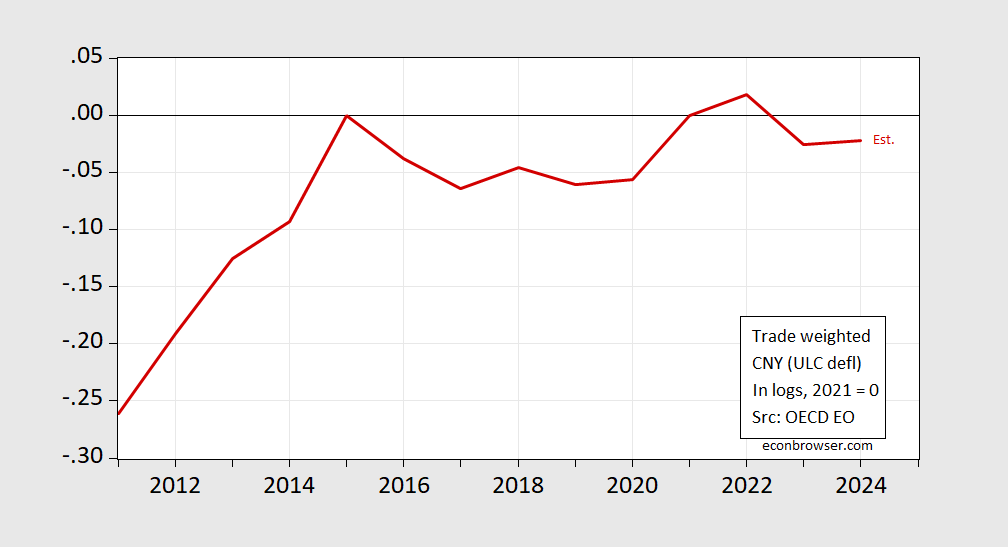

On the point that China is unlikely to let it’s currency appreciate against the US dollar, it’s interesting to inspect not only the CPI deflated yuan (as Sobel does), but also the ULC deflated yuan (this took some hunting around):

Figure 2: ULC deflated value of Chinese yuan (red), in logs 2021=0. ULC is economy wide. 2024 observation is forecast. Source: OECD, Economic Outlook statistical appendix, December 2024.

The Chinese are trying to spur growth in their economy, in part by spurring only exports. Appreciation works against this.

By the way, if indeed the Trump administration plans to slap a 60% tariff on China, just remember the standard deviation of the month-on-month change in the CNY/USD exchange rate (2018-2024) has been about 1.3% ( not annualized). At the possible cost of capital flight, the Chinese could allow substantial yuan depreciation, although as Sobel notes, a more “managed” depreciation might be implemented.

At a minimum, don’t expect a grand plan to arrange euro and yuan appreciation.