With apologies to Kramer’s boss in Seinfeld. From Oren Cass’s “Trump’s Most Misunderstood Policy Proposal: Economists aren’t telling the whole truth about tariffs,” The Atlantic:

Their first mistake is to consider only the costs of tariffs, and not the benefits. Traditionally, an economist assessing a proposed market intervention begins by searching for a market failure, typically an “externality,” in need of correction. Pollution is the quintessential illustration. A factory owner will not consider the widespread harms of dumping pollutants in a river when deciding how much to spend on pollution controls. A policy that forces him to pay for polluting will correct this market failure—colloquially by “making it his problem.” It imposes a cost on the polluter in the pursuit of benefits for everyone else.

Tariffs address a different externality. The basic premise is that domestic production has value beyond what market prices reflect. A corporation deciding whether to close a factory in Ohio and relocate manufacturing to China, or a consumer deciding whether to stop buying a made-in-America brand in favor of cheaper imports, will probably not consider the broader importance of making things in America. To the individual actor, the logical choice is to do whatever saves the most money. But those individual decisions add up to collective economic, political, and societal harms. To the extent that tariffs combat those harms, they accordingly bring collective benefits.

I dunno. I’m not the trade specialist in my forthcoming textbook with Doug Irwin (Cambridge University Press), but I’m pretty sure I talked about to my intro to trade course about transfers, dead weight loss on production and consumption sides, and what the infant industry argument was. I think I also talked about learning-by-doing, and long-run impacts. Checking back, why yes I did: see on tariff transfers to Treasury, DWL here, on infant industry etc., here. (In fact, the fact that Mr. Trump keeps on talking about all the tariff revenue the Treasury would get to replace lost revenue for getting rid of income taxes means that we cannot in general be ignoring the transfers from consumers to Treasury.)

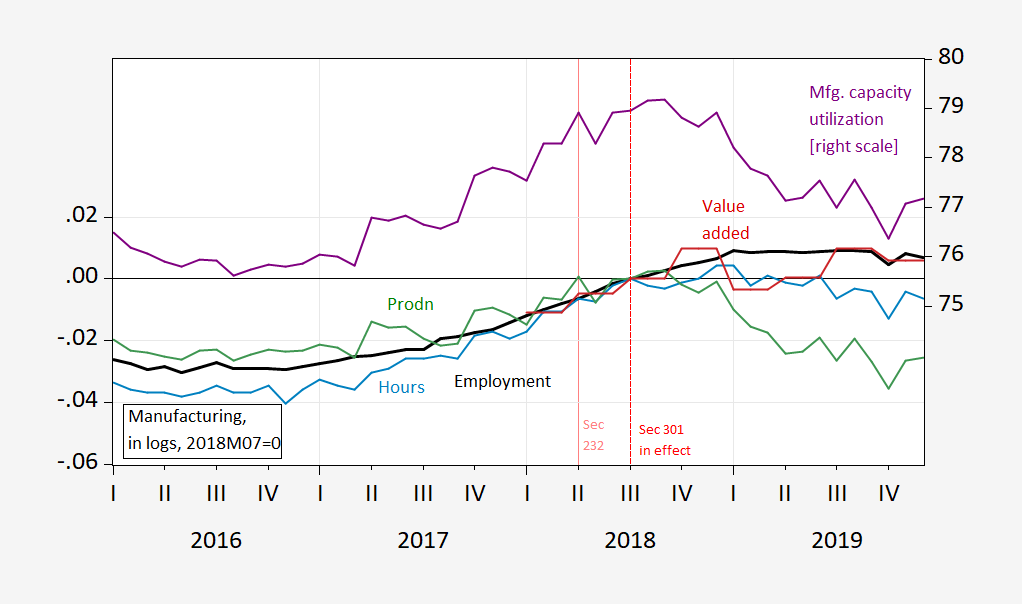

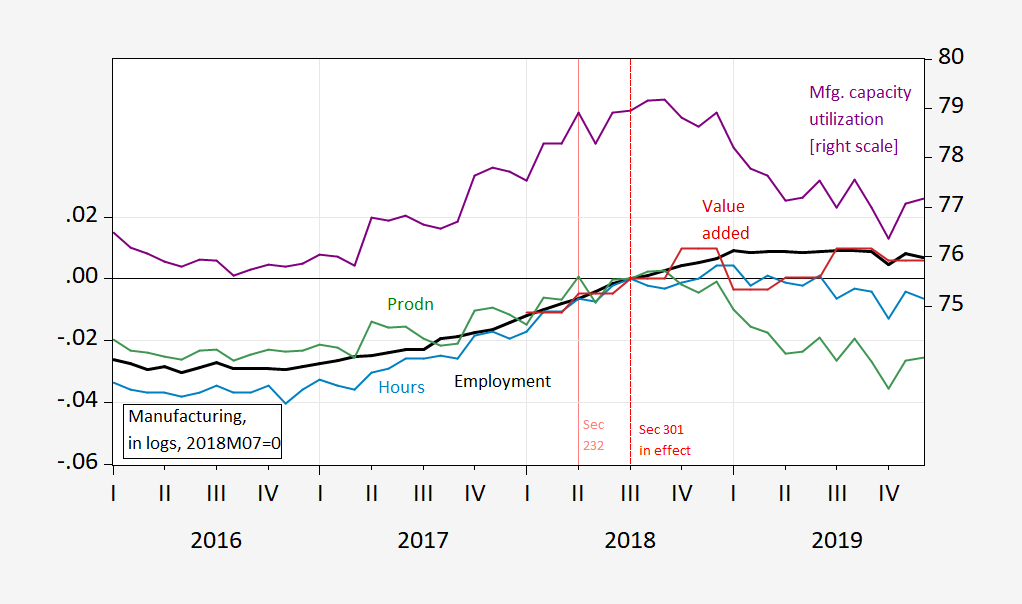

It all comes down to empirics, then, if we’re talking about effects. And here we know what happened to indicators of activity in the wake of the 2018-20 trade war, at least to manufacturing.

Figure 1: Manufacturing employment (bold black, left scale), hours (light blue, left scale), production (green, left scale), valued added (red, left scale), all in logs 2018M07=0; and capacity utilization (purple, right scale). Source: BLS, Federal Reserve, BEA via FRED, and author’s calculations.

See also this assessment of job losses, gentlemen.

So, if Mr. Cass wants to talk about welfare, I’d love to see his calculations of welfare loss to consumers, welfare gains to producers, and transfers to Treasury in short run and long run. He’d have to specify the value of the externalities associated with manufacturing, among other things. I suspect he has little idea of the quantities involved.

And this guy is running the think tank that’s going to provide the ideas for Trump 2.0?